Evolution of Watch Movements: from Classic to Modern

Why Watch Movements Matter More Than You Think

When you look at a watch, you're not just checking the time - you're connecting to centuries of ingenuity, craft, and obsession. Hidden behind the dial, often invisible to the eye, is the movement - the heart of the watch. For those just getting into horology, the concept might seem abstract at first. What's a movement? Isn't a watch just a battery or a wind-up device?

A watch movement is the engine. It's what makes the hands tick, the complications turn, and the entire timepiece function. The same way an engine defines a car, the movement defines a watch's character, purpose, and complexity. Whether it's mechanical, automatic, quartz, or hybrid - what's inside shapes everything you see and feel on the outside.

The reason people care so much about movements isn't nostalgia. It's because movements tell stories. A mechanical movement connects you to centuries of watchmaking tradition, crafted in tiny tolerances by human hands. A quartz movement reminds us how technology made precision available to everyone. A hybrid? That's today's challenge - merging soul with smart tech.

But here's the thing most overlook - watch movements evolved in response to the way people live. When soldiers couldn't pull pocket watches out of their coats in the trenches, wristwatches emerged. When the world demanded precision for less, quartz won hearts. When enthusiasts sought soul over specs, mechanicals returned in force.

This article isn't just a timeline. It's a full explanation of how each era of watch movement reflects the world around it. We'll walk through each generation - not just what changed, but why it changed, and how it affects you as a wearer or builder today.

If you're someone who's curious about starting a DIY build, unsure about which movement to choose, or just tired of shallow listicles that leave you with more questions - you'll feel at home here.

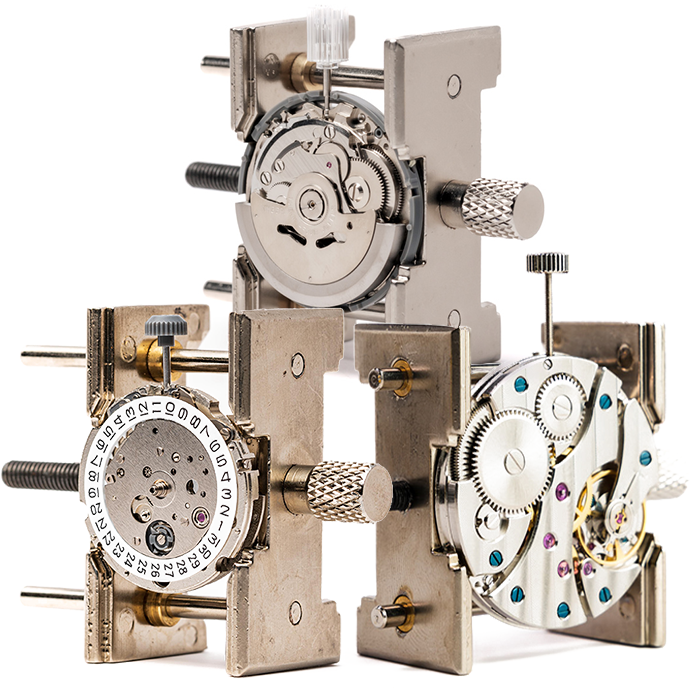

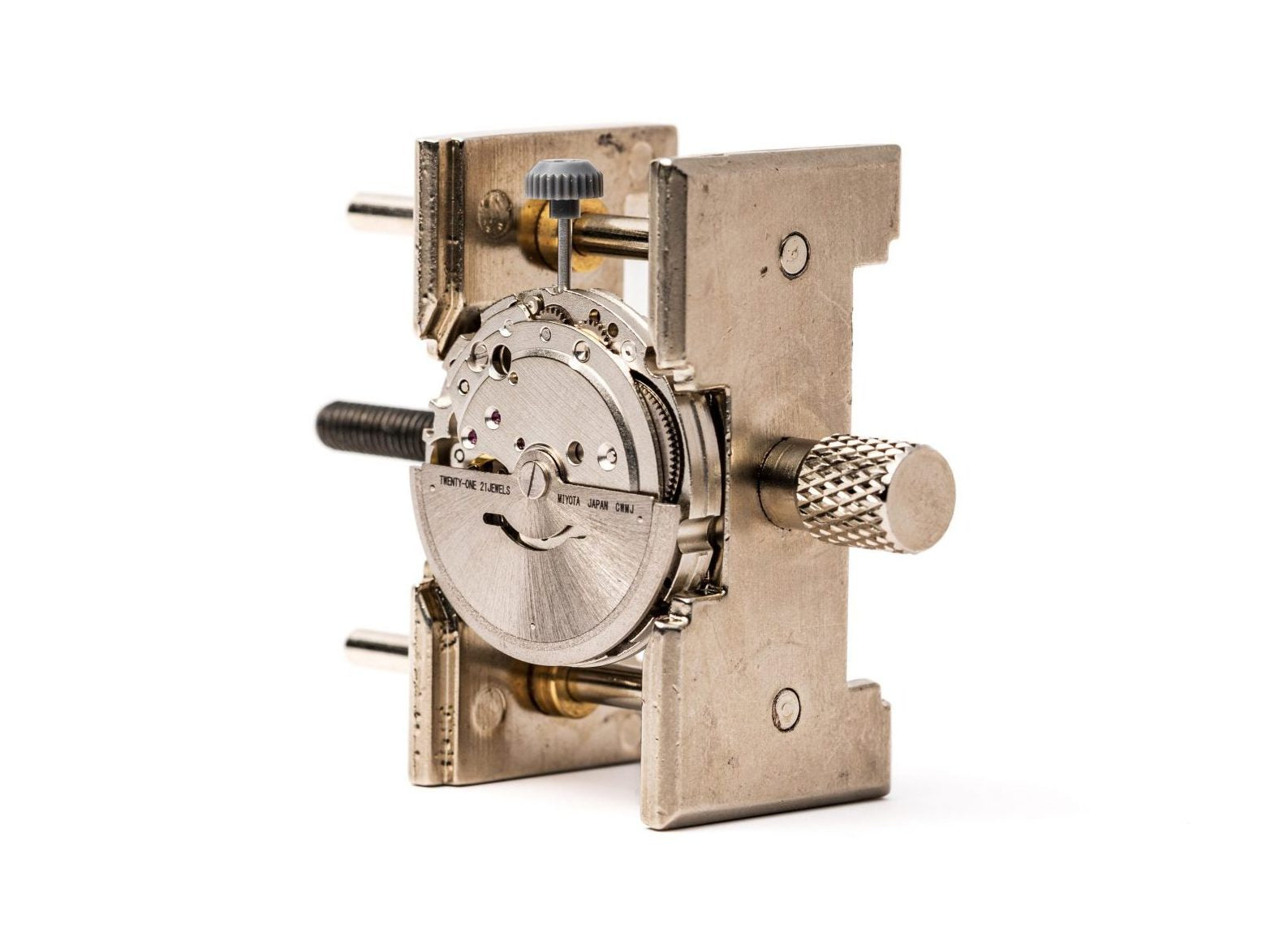

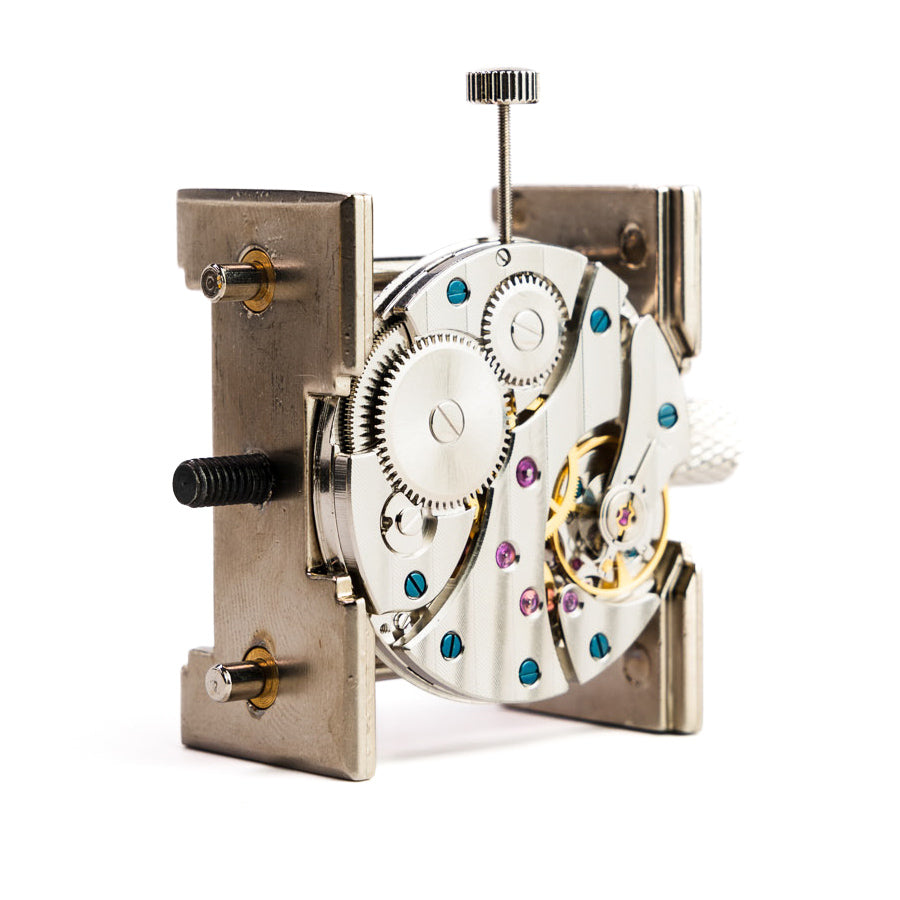

Comprehensive Watch Movement Evolution Overview![]()

The history of watch movements spans several distinct eras, each characterized by unique technological innovations, user experiences, and cultural significance.

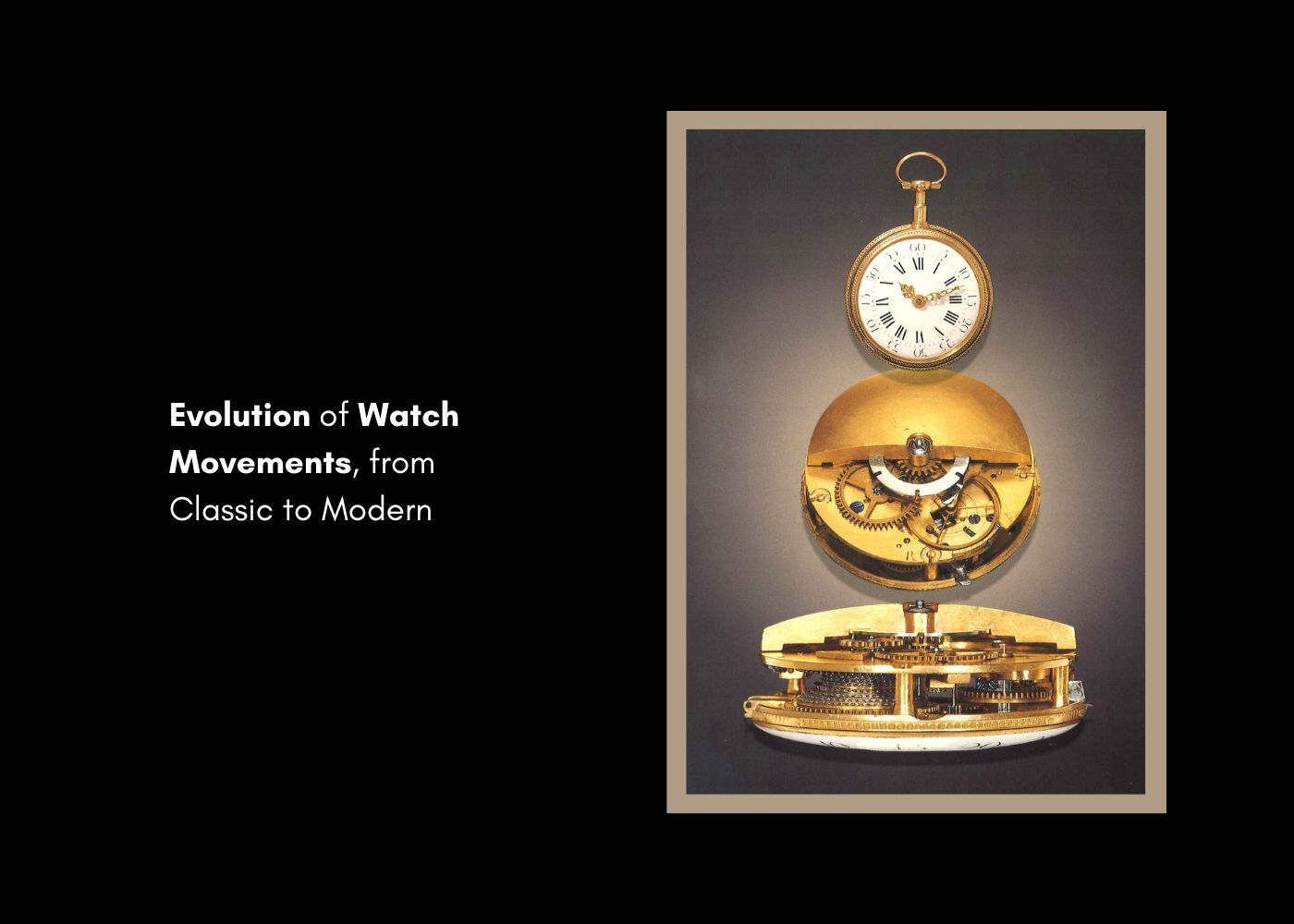

Early Mechanical Era (1600s–1700s)

Watches in this period were powered by hand-wound springs and featured key innovations such as the balance spring, verge escapement, and early gear trains. Their accuracy was poor, often losing or gaining several minutes per day, and they typically offered a power reserve of around 24 hours. Maintenance needs were high, with frequent lubrication required, and the mechanisms were sensitive to wear. Visually, these watches had hidden mechanisms and were primarily utility-driven. The user experience was manual and fragile, making them not very user-friendly. Despite these limitations, this era laid the foundation of mechanical horology.

Pocket Watch Era (1700s–1800s)

Advancements in this era included miniaturization, the introduction of the fusee-and-chain drive, and temperature compensation. These watches continued to use hand-wound springs and achieved moderate accuracy, with deviations of about 30 seconds per day. Power reserves ranged from 30 to 40 hours, and maintenance required regular cleaning and tuning. Aesthetically, pocket watches were known for engraved bridges and decorative early work. Users had to wind them daily, and the watches offered low shock resistance. Culturally, they became status symbols and marked the early personalization of timekeeping.

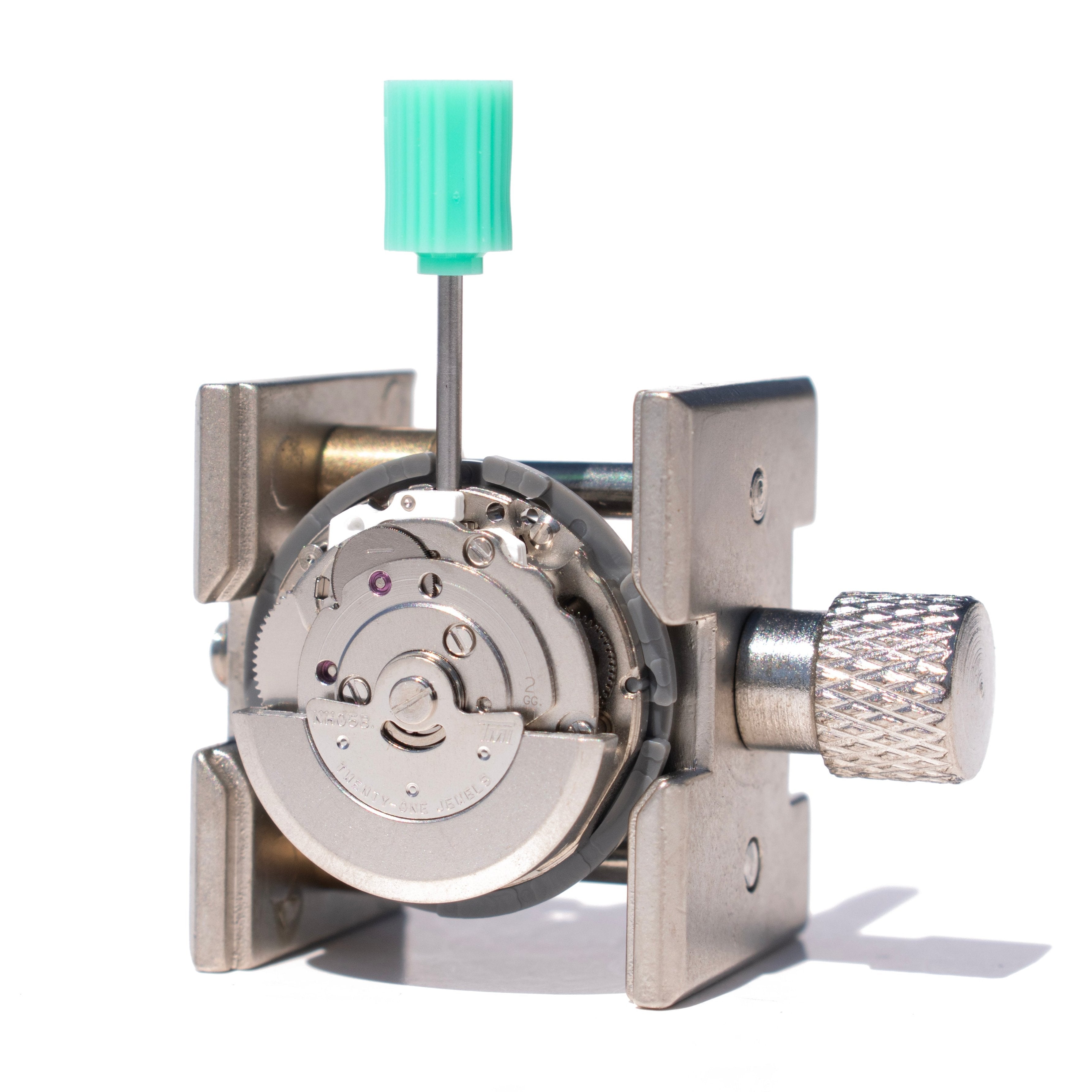

Manual Wristwatches (1900s–1920s)

The transition to wristwatches brought crown-based winding and adaptations of pocket watch calibers for the wrist. Accuracy improved to about 30 seconds per day, with power reserves between 36 and 50 hours. Maintenance remained moderate, with crown issues and wear being common. These watches featured classic dials, domed crystals, and sub-seconds displays. The tactile winding process required manual interaction, making timekeeping a more personal daily ritual. This era signified the entry of modern timekeeping into daily life.

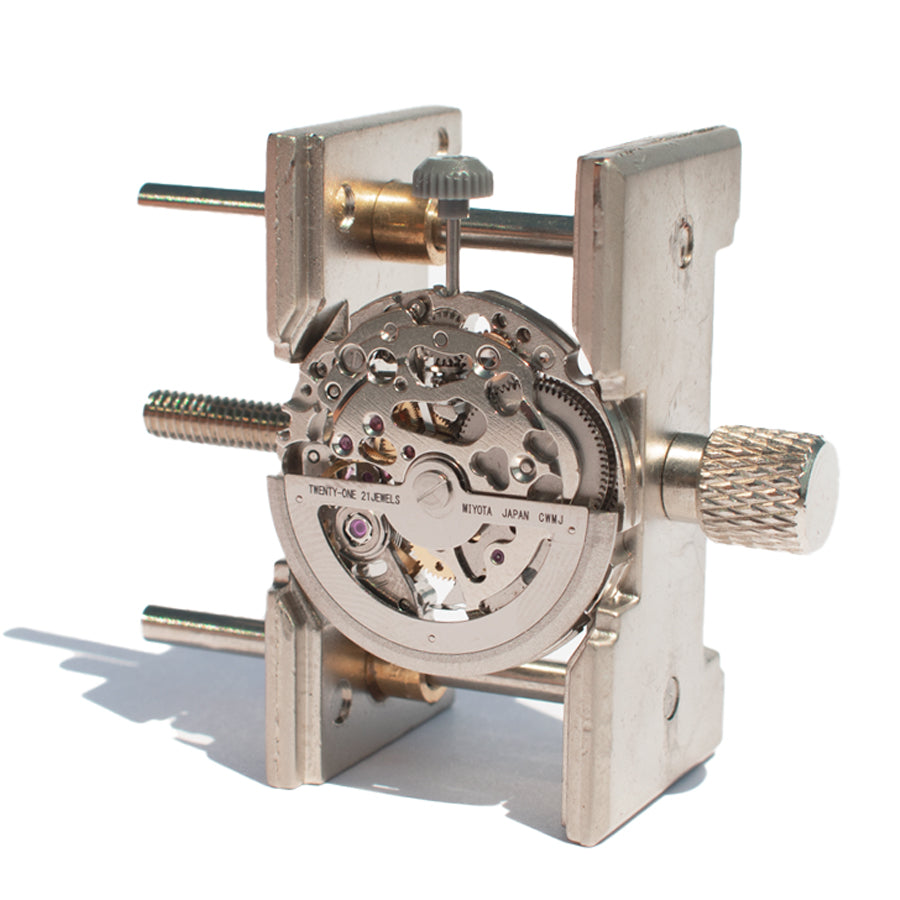

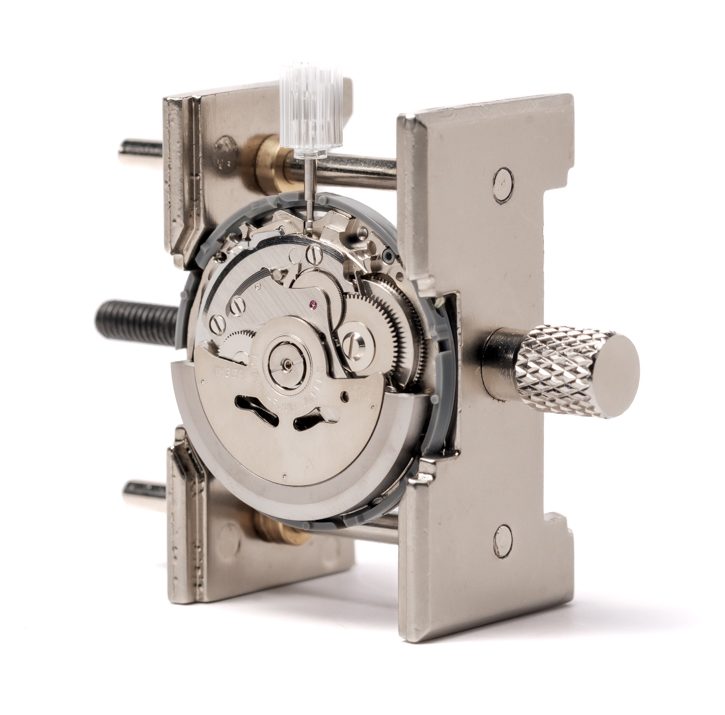

Automatic Movements (1920s–present)

Automatic watches introduced rotor-driven mainsprings with bi-directional winding, ball-bearing rotors, and micro-rotors. Accuracy improved to about 10 seconds per day, and power reserves ranged from 40 to over 80 hours. Maintenance needs were low to moderate, with periodic servicing required for the rotor and gear train. Exhibition casebacks and visible rotors became popular aesthetic features. The user experience shifted to self-winding through motion, making these watches intuitive to wear. This era balanced tradition with convenience.

Quartz Revolution (1969–present)

Quartz watches, powered by a battery and quartz crystal, brought about a revolution with innovations like the quartz oscillator, stepper motor, and integrated circuit control. They achieved excellent accuracy, with deviations of about 15 seconds per month, and battery life typically lasted one to three years. Maintenance was minimal, requiring only periodic battery replacement. These watches featured slim, minimal designs and battery-powered indicators. The user experience was simplified, with no winding needed. Culturally, quartz technology democratized watch accuracy and availability.

Mechanical Renaissance (1990s–present)

This era saw a revival of high-end mechanical watchmaking, powered by hand-wound or rotor mechanisms. Innovations included tourbillons, moonphase complications, and co-axial escapements. High-end calibers achieved accuracy within half a second per day, with power reserves ranging from 48 to 120+ hours. Maintenance was moderate, with less frequent but more costly servicing. Watches from this era often showcased artistic skeleton dials, fine finishing, and sapphire backs. The user experience emphasized emotional connection and ritual, reflecting a renewed appreciation for artistry and storytelling in horology.

Hybrid Movements (1999–present)

Hybrid watches combine mainspring or battery power with electronic circuits, offering features like Spring Drive regulation, mecha-quartz chronographs, and smartwatch syncing. They achieve quartz-level precision with advanced features. Power reserve varies widely: Spring Drive models can last up to 72 hours, while smart hybrids may run for up to two weeks. Maintenance depends on the specific mechanical or hybrid parts, which may require specialized care. These watches typically feature analog displays with smart tech integration, blending useful digital features with classic analog charm. The user experience is enhanced by smart integration and analog appeal, representing the best of both worlds for the connected watch wearer.

Each era of watch movement reflects the technological, aesthetic, and cultural priorities of its time, contributing to the rich tapestry of horological history.

![]()

![]() Early Movements and the Start of Timekeeping's Evolution

Early Movements and the Start of Timekeeping's Evolution

Long before watches ever wrapped around a wrist, timekeeping was a community affair. Towns gathered around clock towers. Monks rang bells. Clocks were massive - the kind you'd hear echoing across a square, not slip into your coat pocket. Precision? It was good enough to get to church on time.

The real shift began when people tried to shrink timekeeping into something portable. That meant new engineering challenges: smaller gears, coiled springs, escapements that could release energy in micro-doses. The earliest portable clocks were spring-driven and relied on verge escapements - crude mechanisms that worked, but only just.

What finally unlocked consistent timekeeping was the invention of the balance spring in the mid-1600s. Think of it as the heartbeat of the watch. Paired with the balance wheel, it created the oscillating rhythm that's still used in mechanical watches today. Whether you credit Christiaan Huygens or Robert Hooke depends on which side of the academic fence you sit - both contributed to this revolutionary concept.

From there, pocket watches became the norm. They were mostly hand-wound, relied on fusee-and-chain or barrel systems, and required careful handling. Accuracy improved over the decades, but temperature, magnetism, and shock remained constant threats. Watchmakers began experimenting with new alloys, better lubrication, and tighter tolerances. It was a race - not just for accuracy, but for miniaturization.

And here's what often gets missed: early watch movements weren't designed to be beautiful. They were hidden under cases, buried behind metal lids. But even then, makers took pride in finishing parts that no one would see. That obsession with detail laid the groundwork for what would become modern haute horlogerie.

If you're starting your own build today and want a movement that honors those traditions, the ST3600 hand-wound movement is a great entry point. Based on the Swiss ETA 6497-1 architecture, it's sturdy, tactile, and offers a direct connection to the past - no rotor, no battery, just pure gear-driven mechanics.

How War, Fashion, and Function Redefined Timekeeping

The pocket watch wasn't abandoned because it failed, it was simply outpaced by the world's changing needs. In the early 20th century, people didn't just need to own time. They needed to access it instantly. War forced urgency. In battle, reaching into your vest wasn't just inconvenient, it could be dangerous.

Soldiers began strapping pocket watches to their wrists using leather holders. This DIY innovation eventually turned into a design revolution. Watchmakers noticed. Cases got smaller, crowns shifted to 3 o'clock, and dial visibility improved. The wristwatch, once a niche accessory for women, became standard-issue masculinity.

What defined this era was the rise of manual-wind wrist movements. These were smaller adaptations of pocket watch calibers, often with the same gear train and escapement, but redesigned for slimmer, more rugged cases. Winding your watch each morning wasn't a chore - it was a ritual.

Brands like Breguet and Patek Philippe helped elevate the wristwatch from tool to treasure. Patek's use of high-complication manual movements turned these tiny machines into objects of desire, not just utility. Dials became more ornate, cases more varied, and casebacks began to reveal the artistry within.

The simplicity and interactivity of manual movements are still a huge draw for watchmakers today. You feel each click of the crown. You understand when it's running low. You build a relationship with it - something no smart device can replicate.

If you're new to watchmaking and want to start building, pairing an ST3600 with the Raised Pure White Dial offers that classic wristwatch vibe: simple, legible, and tied to a moment in time when engineering began to meet emotion.

How Automatic Movements Changed the Game Without Changing the Rules

Once wristwatches became the new norm, the next challenge was obvious: what if you never had to wind your watch again? The daily ritual, while charming to some, was a limitation for many. Miss a day or two, and your watch stopped. Set it again. Wind it up. Repeat.

The solution came from motion. In 1770, Abraham-Louis Perrelet designed a pocket watch that wound itself using a swinging weight inside the case. But it wasn't until John Harwood's 1923 invention - the first self-winding wristwatch - that automatic movements found their purpose. Harwood's idea was simple: leverage the natural motion of the wrist to wind the mainspring.

The real breakthrough was Rolex's Perpetual rotor in 1931. This unidirectional, semi-circular weight spun freely on a pivot and wound the mainspring as the wearer moved. It was elegant. It was efficient. And it worked. From that point on, automatic watches became a gold standard - combining the soul of mechanical watchmaking with the convenience of a powered rotor.

The appeal of automatic movements lies in their independence. You wear them, they run. Leave them on the dresser too long, and yes - they'll stop. But on your wrist, they feel alive. The rotor spins silently as you go about your day, capturing motion and storing energy.

Designers soon began experimenting with rotor types. Some movements feature a full-sized central rotor. Others, like those in ultra-thin watches from Piaget, use micro-rotors embedded into the movement plate. And then there's the peripheral rotor - mounted on the outer edge, leaving the rest of the movement visible beneath a sapphire caseback. Pure theatre, but with mechanical logic.

Automatic movements also introduced the concept of the power reserve. Most run between 40 to 50 hours once fully wound - just enough to get you through the weekend. High-end movements can store several days of energy. Some, like the A. Lange & Söhne Lange 31, boast a full month of autonomy.

For those building watches today, automatic movements are ideal when convenience matters. If you like seeing movement in action but don't want to reset your watch each day, a well-made automatic is a great choice. And if you want to stick to the foundational mechanics but showcase their beauty, pairing a manual like the ST3600 with the Skeleton Dial lets you fully experience the energy pathway - from crown to mainspring to gear train.

Automatic movements didn't kill manual-wind watches. Instead, they carved out their own domain - a middle ground between the hands-on nature of vintage horology and the lifestyle flexibility modern users wanted.

How Quartz Redefined Accuracy, Access, and the Industry Itself (Quartz Crisis)

When people talk about disruption in the watch world, nothing hits harder than quartz. The 1969 launch of the Seiko Astron didn't just introduce a new type of movement - it introduced a new idea: that a wristwatch could be more precise, more affordable, and require zero winding.

Quartz movements rely on a tiny crystal vibrating at 32,768 times per second. This frequency, stabilized by an electric circuit and powered by a battery, drives a step motor that turns the watch hands. Compared to even the best mechanical watches, quartz is breathtakingly accurate - usually deviating by only a few seconds per month.

For most consumers, that wasn't just impressive - it was revolutionary. Watches no longer needed servicing every few years. They didn't stop overnight. They were slimmer, lighter, and cheaper to produce. Suddenly, everyone could own a timepiece that rivaled Swiss chronometers in accuracy.

But for the Swiss watch industry, the so-called "Quartz Crisis" was devastating. Many heritage brands collapsed. Others merged to survive. Those that remained had to decide: join the quartz wave or double down on traditional craftsmanship. Companies like Swatch emerged by embracing quartz in playful, mass-market designs. Others, like Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet, leaned hard into mechanical luxury.

The quartz era didn't just change movements - it changed expectations. The market split. Some consumers began to expect perfect accuracy, long battery life, and zero fuss. Others started to value the craftsmanship behind mechanical watches even more, seeing quartz as too clinical, too emotionless.

And here's the nuance most miss: quartz didn't kill mechanical - it forced it to evolve. The renaissance of luxury mechanical watches in the 1990s happened because of quartz. The contrast made the craftsmanship stand out more. Suddenly, a tourbillon wasn't just impressive - it was a statement of resistance against disposable tech.

Quartz is still a great choice for many users today. It's reliable, affordable, and almost zero-maintenance. For anyone who just wants a no-nonsense timekeeper - or for those with large collections who rotate watches often - quartz keeps the whole setup smooth.

You won't build a quartz movement from scratch, but you'll still appreciate what it represents. It's a reminder that innovation in watchmaking doesn't always come from tradition - sometimes it comes from rethinking the question entirely.

The Mechanical Renaissance & Resurgence of Mechanical Watches

Quartz watches may have won the precision battle, but they couldn't replace the feeling of a mechanical watch. For a while, it seemed like they might. The 1970s and 80s were rough for traditional watchmakers. Brands disappeared. Movements were shelved. Factories closed. But something unexpected happened in the decades that followed.

People started to miss the connection. The craftsmanship. The stories behind the components. The satisfaction of winding a watch in the morning. And slowly, mechanical watches started making a comeback - not because they were better in every measurable way, but because they offered something quartz couldn't: intimacy.

Luxury brands led the way. Companies like Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, and A. Lange & Söhne refocused on high complication pieces - watches with perpetual calendars, tourbillons, moon phases, and minute repeaters. These weren't just timekeepers. They were moving sculptures. Art with a heartbeat.

Collectors followed. As quartz flooded the market with $50 watches that kept perfect time, mechanical pieces became something rarer. Owning one signaled not wealth, but understanding. Appreciation. Patience.

And that appreciation wasn't limited to luxury buyers. The resurgence inspired independent watchmakers, microbrands, and even DIY enthusiasts. People wanted to build, repair, and customize their own mechanical watches. Kits like the Seagull ST3600 made this accessible, allowing anyone with a steady hand and curiosity to put together a working movement. It's not just a project - it's a conversation with every watchmaker who ever came before you.

This mechanical renaissance wasn't a trend - it was a shift in perspective. Accuracy was no longer the only metric. Now people cared about feel, rhythm, and connection. They wanted to hear the tick. To watch the escapement beat. To know that what powered their watch wasn't a chemical cell, but a tightly coiled spring and a cascade of micro gears.

Today, mechanical watches occupy a different space entirely. They're not here to compete with quartz. They're here to offer something quartz never will: the experience of time being physically kept - not just digitally counted.

Blending Analog and Digital - The Rise of Hybrid Movements

Just when it seemed like mechanical and quartz were two completely separate worlds, watchmakers started to experiment with something in between. Movements that combined the charm of gears with the brains of circuits. These hybrids weren't about choosing one or the other - they were about asking what happens when you combine both.

One of the most innovative examples came from Seiko, again. The Spring Drive, first introduced in 1999, is a movement that's powered by a traditional mainspring, like a mechanical watch - but regulated by a quartz oscillator and an integrated circuit. It doesn't tick. It glides. Smoothly. Quietly. Perfectly. It's the closest thing to seeing time flow.

Hybrid movements don't stop at Seiko. Some watches use mecha-quartz movements - chronographs where the main timekeeping is quartz, but the stopwatch is mechanical. You get the crisp snap of a mechanical pusher, but the reliable timekeeping of a battery.

And then there are hybrid smartwatches. Not full-screen wearables, but analog-looking watches that connect to your phone. Think Frederique Constant Hybrid or Withings Steel HR. These watches track your steps, monitor your sleep, and give you gentle notifications - all while looking like a classic timepiece.

For those who love traditional design but want modern features, these hybrids offer the best of both worlds. You're not forced into a black screen or short battery life. You get real hands, real dials, and quiet intelligence behind the scenes.

Hybrids also reflect something deeper: that technology and tradition don't have to compete. They can complement each other. You can have a movement regulated by quartz without sacrificing the soul of mechanical energy. You can wear a watch that tracks your health without looking like a gadget.

If you're designing your own watch and want to embrace both styles, consider mixing mechanical aesthetics with modern materials. Dials like the Black & Gold Minimalist Dial give you clean lines and contemporary style - a perfect visual match for hybrid builds.

Hybrid movements aren't a compromise. They're a response to the modern user - someone who wants presence on the wrist, but also functionality in daily life.

How Material Science is Redefining the Way Movements Are Built

At the heart of modern watchmaking is a quiet revolution in materials. For centuries, movements relied on brass, steel, and ruby jewels. And while those materials still dominate, the demands of durability, magnetism resistance, and long-term reliability have forced watchmakers to look deeper into the periodic table.

Silicon is one of the biggest breakthroughs in the history of watch movements. It's antimagnetic, incredibly lightweight, and requires no lubrication. That makes it perfect for delicate, high-friction parts like the escape wheel and pallet fork. Brands like Omega, Patek Philippe, and Ulysse Nardin now use silicon components in their most accurate timepieces - not for marketing, but because it works.

LIGA technology (short for Lithographie, Galvanoformung, Abformung) has also changed the game. This micro-manufacturing process allows components to be made with incredible precision - down to the micron - enabling smaller tolerances and better shock resistance in modern mechanical movements. It's not something you'll see on a spec sheet, but it's why some movements feel smoother, last longer, and run cleaner.

Even materials like ceramic and carbon fiber are making their way into internal watch parts. Ceramic ball bearings reduce friction in automatic rotors. Carbon fiber bridges offer strength with no weight penalty. These aren't gimmicks - they're responses to real problems like wear, temperature shift, and lubricant degradation.

When you're assembling a movement yourself, most kits still rely on traditional metals - and that's okay. For example, the ST3600 is engineered for accessibility and classic reliability. But the future? That's being built atom by atom, with materials designed to outlast generations.

What are Escapements in a Mechanical Watch?

If the mainspring is a movement's muscle, the escapement is its brain. This small set of parts - usually the escape wheel, pallet fork, and balance wheel - regulates how energy is released from the wound spring into the gear train.

Without an escapement, your watch would unwind in seconds. With it, the release of energy happens one beat at a time - turning circular power into time itself.

The oldest escapement designs were rudimentary. Verge escapements date back to the 13th century and were used in early tower clocks. They were large, inaccurate, and noisy - but they introduced the idea of controlled release.

The lever escapement, developed in the 18th century, became the gold standard - and it still is. Its beauty is in its balance: two pallets alternately lock and unlock the escape wheel, giving the balance wheel its impulse and allowing consistent beats per hour.

More recently, escapement innovation has focused on reducing friction and increasing efficiency. The co-axial escapement, invented by George Daniels and adopted by Omega, splits the locking and impulse functions into separate components. That reduces contact, minimizes wear, and delays the need for lubrication - a true game-changer in long-term reliability.

In movements like the ST3600, you're working with a traditional Swiss lever escapement. It's reliable, durable, and still serves as a masterclass in mechanical logic. When you assemble one yourself, it's the escapement that brings the moment of truth - when the balance starts to swing, and the movement comes to life.

Key Takeaways

Each type of movement emerged not from trend, but from need. People demanded smaller, more wearable watches. Then they needed convenience, then precision, then connection. Movements changed because lives changed.

Mechanical movements still exist not because they're better - but because they're deeply human. They reflect our desire to feel time passing. To interact with it. To own a tiny engine beating away beneath glass and steel.

Quartz taught us that innovation doesn't have to look traditional. And hybrid movements showed that you don't have to choose between classic and modern - you can have both.

Material science and escapement innovations are shaping the future. Not just in terms of performance, but longevity and repairability - two values that matter deeply to today's builders.

If you want to truly understand watches, start with what powers them. That's where the story begins - and where the magic lives.

Why Rotate Watches Helps You Build From Within

When you're learning watchmaking, the last thing you need is friction. That's where Rotate comes in. We don't just sell parts. We offer a system - one designed to guide you from novice to confident builder.

Our movements like the ST3600 are quality-checked and shipped from Los Angeles, built on the reliable ETA 6497-1 platform - perfect for your first build, or even your fifth. Combine that with open-dial options like the Skeleton Dial or clean modern finishes like the Black & Gold Minimalist Dial, and your build becomes more than a learning exercise - it becomes a watch worth wearing.

We offer lifetime support, U.S.-based shipping, and community-driven resources. From guides to classes, we believe watchmaking should be accessible, personal, and deeply rewarding.

You're not just buying parts. You're building your own time. That's the Rotate difference.

FAQ

Q. How do I clean my steel watch strap?

A quick rinse with warm water and mild soap is usually enough. Use a soft brush to get between the links. Dry it thoroughly with a microfiber cloth. For long-term care, check that the clasp functions smoothly and there's no gunk at the joints. If you're starting out, our Mesh Chain-Link Stainless Steel Strap is both stylish and easy to clean.

Q. What maintenance does a steel strap require?

Avoid saltwater, perfume, and lotion build-up. Every few months, remove the strap and clean the area around the lugs. Check for loosened screws or stretched links.

Q. Which watch movement is right for my first build?

Manual movements like the ST3600 are ideal. They're simpler to assemble, don't require rotor clearance, and are easier to regulate. You also get a deeper understanding of how gear trains, escapements, and mainsprings work.

Q. Are hybrid movements difficult to service or build?

Yes - most hybrids are not DIY-friendly. Spring Drives and smart hybrids require specialized equipment and factory servicing. If you're new, stick with mechanical or mecha-quartz options that offer serviceability and transparency.

Q. Can I switch straps between builds?

Absolutely. Choose cases with standard lug widths and look for quick-release straps like our genuine leather bands for easy swapping. It's a great way to give your watch a different personality for different occasions.